The following are Teacher Zhang’s teaching notes.

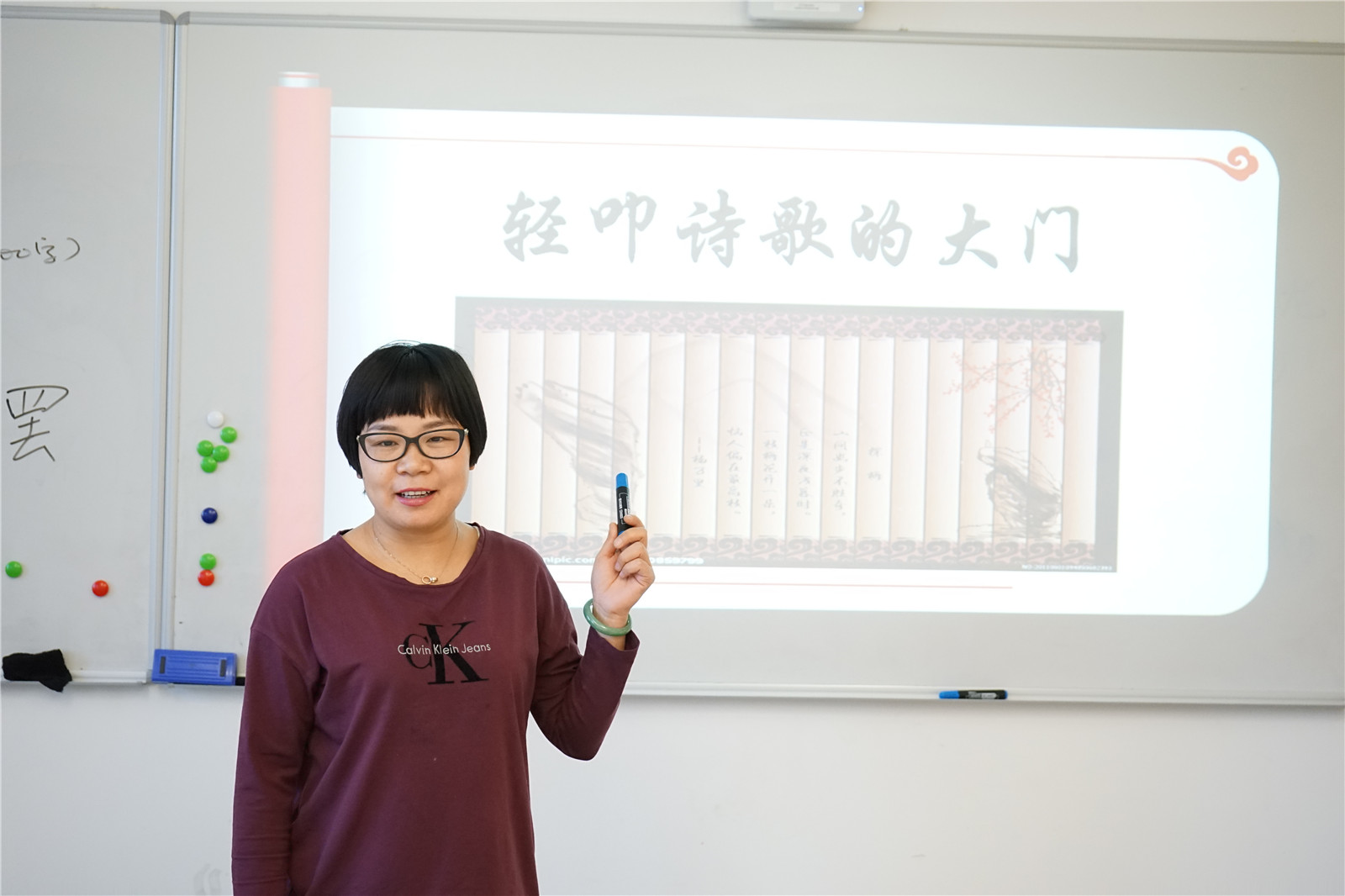

Knock on the Door of Chinese Poetry

By Zhang Kun

Before holding this activity, I was thinking that although our students start to learn ancient Chinese poems at a very young age (even before they are born) and they can memorize a large number of them, they do not understand these poems, nor have they bothered to discover the charm, beauty, and thoughts of these poems. Most of them just want to be an “obedient” child, because their parents and teachers have told them it is important to memorize ancient Chinese poems.

In view of this, I set the goal of this activity—shaking hands with ancient Chinese poems, guiding the children in understanding more about the profound meaning of ancient poems, and leading the children in a dialogue with ancient poets across time and space.

Then I started to design this activity.

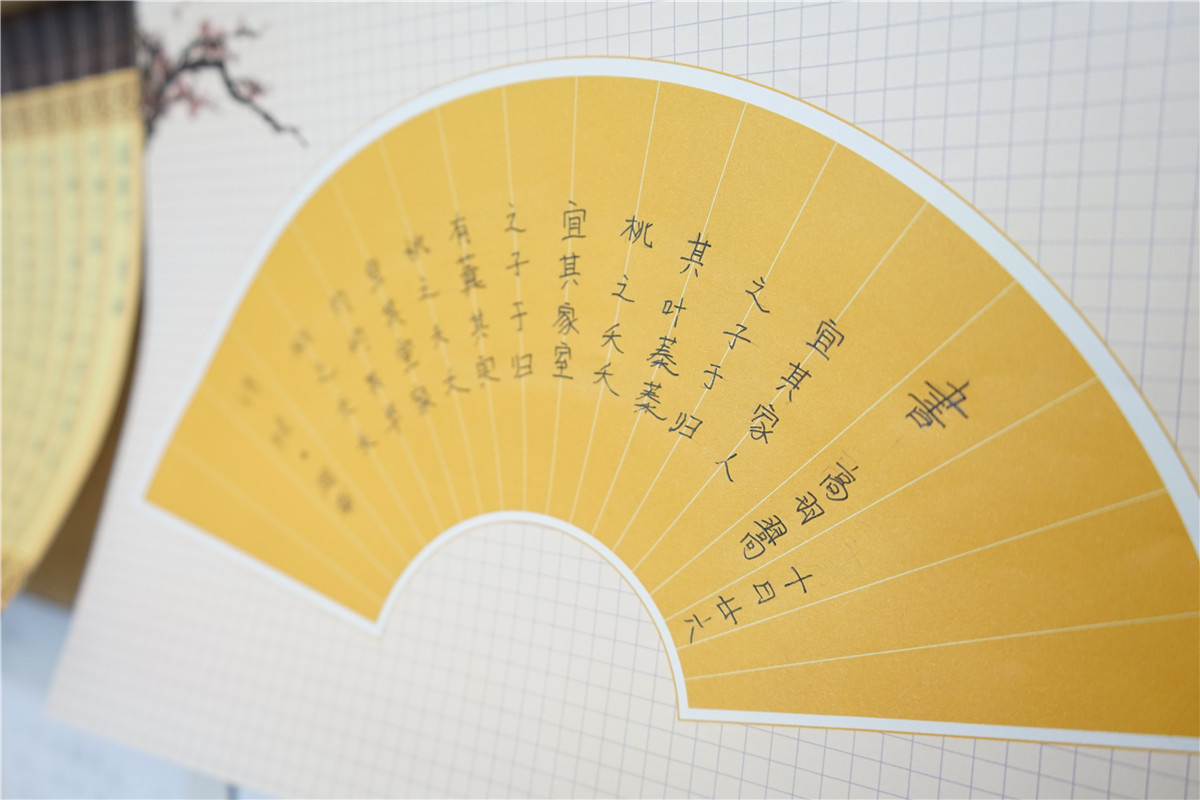

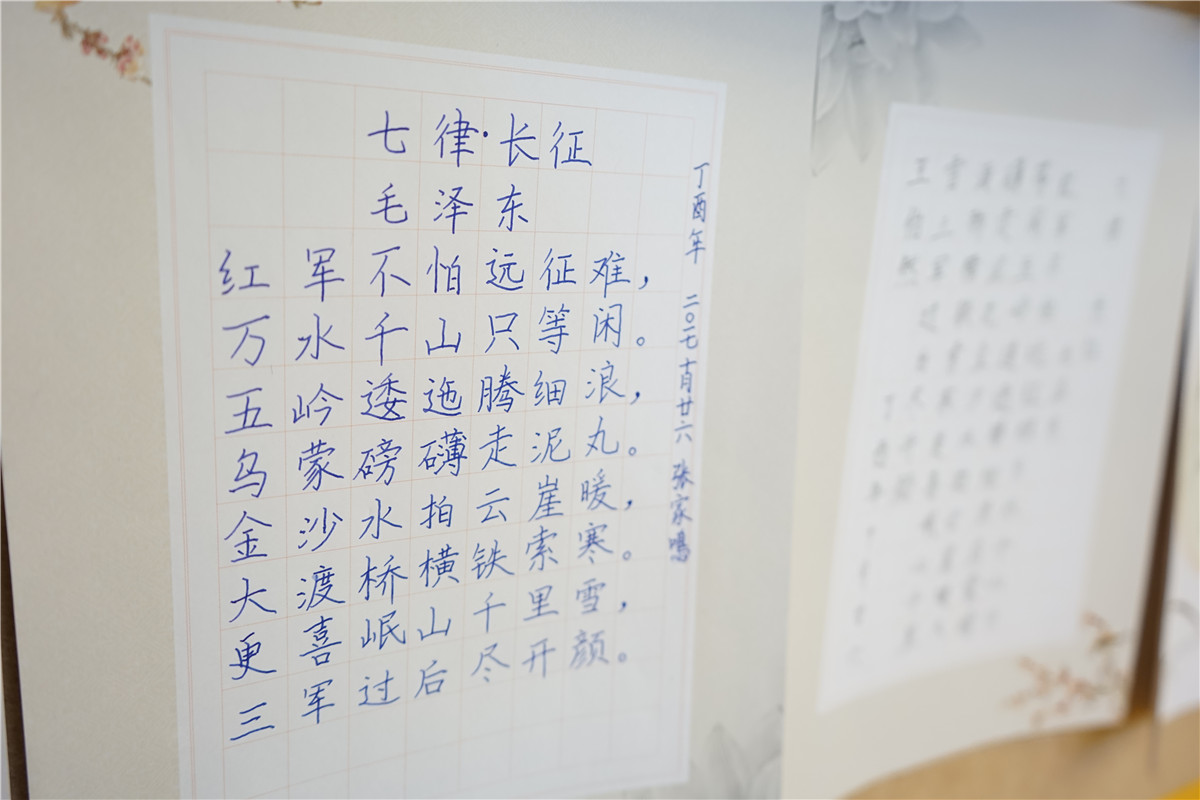

Calligraphy is a visual form of Chinese culture, and lots of the children have come into contact with it from an early age. I organized a hard-pen ancient poem calligraphy competition to “open the door to poetry.” The archaistic pieces of calligraphy paper visually stimulated the children to explore the artistic charm of the Chinese language.

Step 2: Sing a song adapted from an ancient Chinese poem to stimulate enthusiasm.

I asked the children to learn to sing a song adapted from an ancient Chinese poem. The children participated in this activity with great enthusiasm and as a result had a new understanding of ancient Chinese poetry.

Step 3: Introduce interesting and beneficial topics.

The “Interesting Ancient Poems and Knowledgeable Ancient People” topic was both interesting and informative. It was mainly about how ancient Chinese people used Chinese characters to create word game-like poems, such as “acrostic poems” (an acrostic is a poem or other form of writing in which the first letter, syllable, or word of each line, paragraph, or other recurring feature in the text spells out a word or a message), “palindrome poems”, “riddle poems”, and “poems with repeated words.” This activity has allowed the children to feel the unique charm of the Chinese language and the fun of ancient Chinese poems.

© Learning to compose ancient-style Chinese poems in interactive classes

Step 4: Give ingenious lectures to deepen the students’ understanding of ancient Chinese poems.

In this step, I gave the children a three-period lecture entitled “The History of Chinese Poetry.” This lecture, despite a title that implies boring theoretical content, is actually about big events and unofficial anecdotes concerning poetic creation in Chinese history. The lecture had the history of Chinese poetry as the main theme and the development of Chinese society as the secondary theme. Through this lecture, the children had a better understanding of Chinese poetry and its history.

Step 5: Guide the creation of ancient-style Chinese poems—a time to witness surprises.

By now, the children could not wait to create their own poems. To make hay while the sun shines, I started to tell the children the differences between ancient-style poems and modern-style poems, as well as the rhyme and antithesis requirements for jueju (a poem of four lines, each containing five or seven characters, with a strict tonal pattern and rhyme scheme) and lüshi (a poem of eight lines, each containing five or seven characters, with a strict tonal pattern and rhyme scheme).

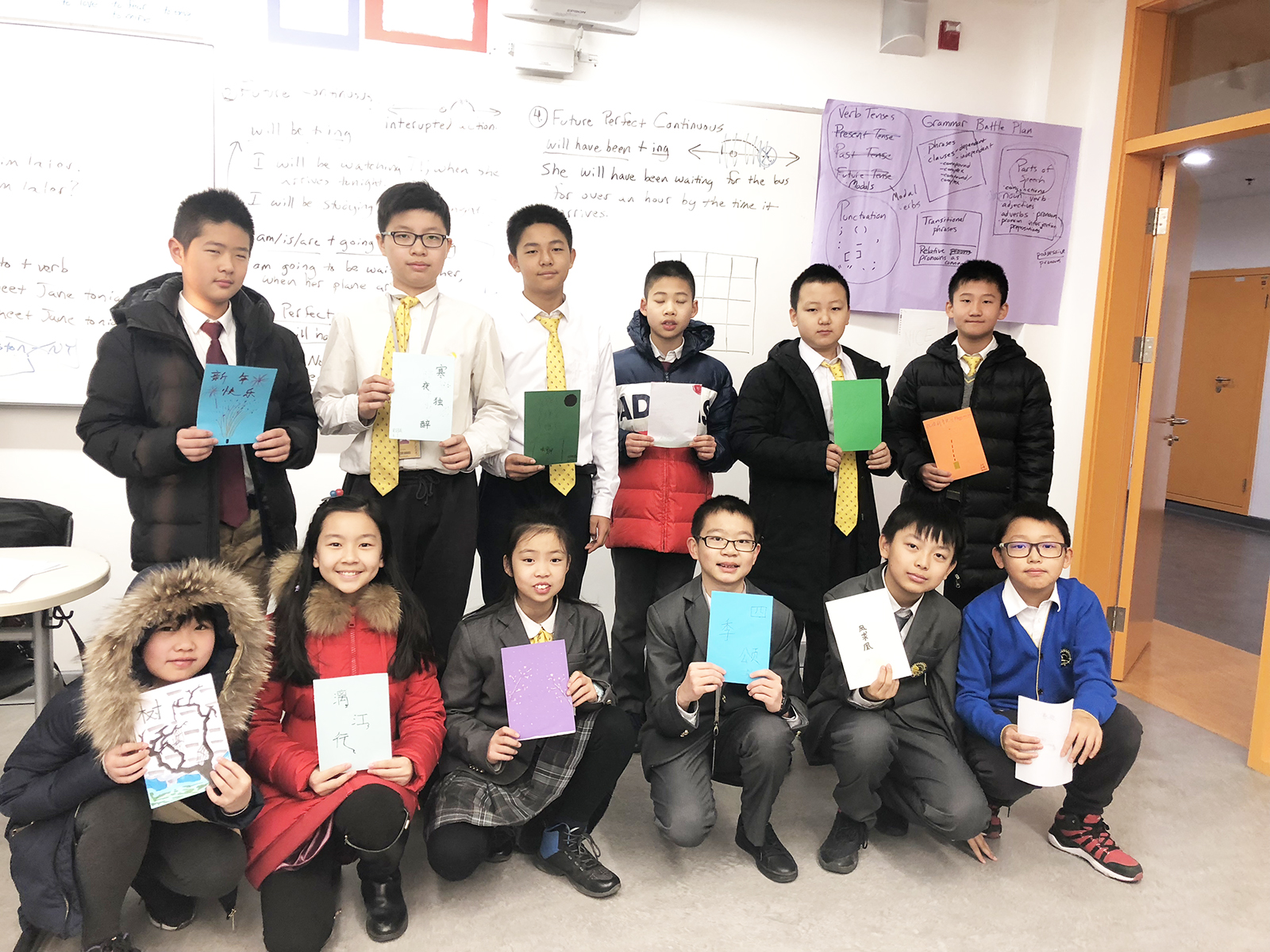

Unexpectedly, the children were very creative and wrote quite presentable ancient-style poems. We then singled out the best ones to encourage more children to compose such poems.

This activity has achieved unexpected results. A child composed an acrostic poem to hide his wishes for his father’s birthday in the poem. Some children became addicted and developed a habit of composing a poem each day, and still some racked their brains for the right word so much so that they forgot to eat and drink.

As a teacher, I consider it my greatest achievement and happiness if the children can really appreciate the beauty of Chinese poetry, grasp the profound connotations of the Chinese language, and feel the charm of the various art forms derived from the language.

Postscript

The new Chinese curriculum standards for compulsory education for junior high school students state: “The Chinese curriculum should be devoted to the formation and development of students’ Chinese literacy. Chinese literacy is the basis for the students to learn other subjects well and the basis for their all-around and lifelong development. The multiple functions and foundation role of the Chinese curriculum have determined its important position in China’s nine-year compulsory education system.”

The sixth graders, who, inspired by ancient Chinese poems, can create creative and beautiful poems in Teacher Zhang’s classes, are advancing toward a life of “poems and dreams.” We have every reason to believe that developing the children’s creativity and imagination by encouraging them to express themselves in the language of poetry means laying a solid foundation for these children’s all-around and lifelong development. This is one of the biggest features of Chinese classes at Beijing Kaiwen Academy and is also the reason why so many students like having Chinese classes.